This article covers the dyeing of wood with chemicals.

It includes the history of natural and synthetic dyes, the uses of chemical dyes, a list of common chemical dyes with their properties, and a list of woods with their recommended chemical dye applications.

The History of Natural Dyes

Coloring wood by chemical means precedes the use of modern synthetic dyes.

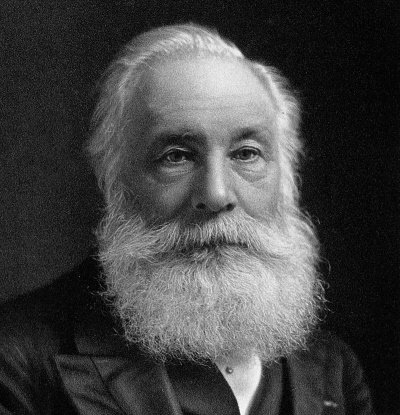

Before the synthesis of the first dye in 1856 by William Henry Perkin, all dyes used on wood and textiles were of vegetable origin, particularly those derived from certain trees, roots, and flowers.

These extractive dyes had several problems.

The first was that they were fugitive or susceptible to fading in sunlight.

Secondly, they washed out easily with water which is a big problem if you wash your clothes.

It was eventually discovered that if the item to be dyed was treated before or after dyeing with various chemicals, the resultant color was deeper, less fugitive and colorfast.

The chemicals employed for this purpose were termed mordants, a word from the French verb mordre, which means “to bite”.

The use of this word illustrates the collective scientific understanding of the times.

Dyers thought that the mordant bit, or opened up the textile- allowing the dye to penetrate and “stick”.

Today, we know that the behavior of these mordants is chemical in nature – they either combine with the dye to form compounds within the substrate being dyed which are more lightfast and colorfast or they act as chemical “binders” to force the dye to attach itself to the structure of the textile.

Natural dyes used with mordants have been found on textiles dated as early as 1700 BC It was the discovery of mordants which was crucial to the development of natural dyes.

The various chemicals employed to fix the colors from these dyes were undoubtedly closely guarded secrets among the various shops and guilds.

The Birth Of Synthetic Dyes

William Henry Perkin synthesized the first synthetic dye, mauve, by reacting aniline with acidified potassium dichromate.

Although this discovery revolutionized the science of organic chemistry, like many other discoveries it was an accident.

Perkin was attempting to synthesize quinine, a drug used at the time to treat malaria.

This “invention” clearly ranks in historical importance as the birth of the era of synthetic dye manufacture.

Other colors soon followed, and to distinguish the new synthetic dyes from the older colorants they were termed aniline or coal-tar colors.

Aniline is a chemical derived from coal-tar, which is a byproduct of the burning of coal.

No doubt many craftsman of the time were reluctant to try the “new” dyes and one can speculate that the use of natural dyes and chemicals for coloring wood continued well into the first part of the twentieth century.

Why Use Natural Dyes And Chemicals?

So why would anyone want to use natural dyes when the synthetic ones are better? There are several reasons.

First, the natural dyes produce coloring within the wood that cannot be duplicated by synthetic dyes.

The color produced is the result of a chemical reaction that takes place within the fibers of the wood, resulting in dramatic and vivid colors.

Secondly, chemical coloring treatments such as nitric acid and ammonia fuming are the only way I’ve found to successfully duplicate the color and patina of aged wood.

Chemical coloring does not emphasize ray-fleck and figuring in hardwoods the way that stains and dyes do.

On softwoods, the darker winterwood is not as emphasized.

These characteristics can be invaluable in reproduction and restoration work.

Dyes And Chemicals Used

In woodworking, the natural dyes of concern are walnut husks, logwood, brazilwood, sumac, cutch and fustic (yellowwood).

These are usually available as extracts or in crystal form.

There are countless other dyes available, but they can be expensive (cochineal and madder) and some involve lengthy preparation before use.

The dyes mentioned above are the ones I’ve found most useful.

They are dissolved in water and are always used with mordants.

The mordants are Potassium Dichromate, alum, copper sulfate, ferrous sulfate, and stannous chloride.

Some of these chemicals may be used without the natural dyes mentioned since they react with the tannic acid naturally present in certain woods.

In addition, there are several other chemicals not classified as mordants, but they have excellent coloring abilities when used on wood.

These are ammonium hydroxide (ammonia-28%), sodium hydroxide (lye), sodium carbonate, and nitric acid.

Another chemical is called vinegar buff and is easily be made in the shop.

Using Chemicals And Dyes

While most of the natural dyes are relatively safe, almost all of the mordants are hazardous.

The acids and alkalis are also extremely corrosive and toxic.

Handle the chemicals with great care and caution.

Safety items such as a good pair of neoprene gloves resistant to chemicals, a cartridge-type vapor mask designed for chemical vapors and safety glasses are mandatory.

A well-ventilated work area is necessary, and when using ammonia and the acids I suggest doing most of the work outdoors.

Finally, a safe, secure storage area out of the reach of pets and children should be available for the chemicals.

Following is a list of various dyes and mordants.

Note of Caution:

When preparing the chemicals below, wear a respirator, safety glasses and gloves.

In powdered and form and solution, the chemicals are poisonous and can be harmful if inhaled, ingested or absorbed through the skin.

In solution, they can be easily absorbed through the skin so I recommend a good pair of neoprene gloves.

I also recommend the use of hot distilled water.

Be sure to date each container and include the concentration, i.e., two ounces to one pint of water.

Careful record keeping and labeling will avoid confusion later.

The natural dyes are available as an extract or the natural product in chips or bark.

I prefer extracts because they are easier to use and don’t require lengthy preparation.

Alum

(aluminum potassium sulfate) Is a mordant used with natural dyes.

It has little coloring effect on its own (compared to potassium dichromate and other mordants).

Use one ounce to one quart water.

Brazilwood

From Brazilwood trees, this natural dye is available as an extract of chips.

Always use with a mordant.

It produces reddish browns.

Use potassium dichromate, ferrous sulfate and stannous chloride as mordants.

Copper Sulfate

Use as a mordant with the various dyes.

Does not have any appreciable coloring when used on its own, but it can be used to kill hot reds produced by other chemical means. Dissolve one ounce in one quart of hot distilled water.

Cutch

A natural dye available as an extract – use with various mordants to produce yellow browns.

Ferrous Sulfate

Use as a mordant with any of the natural dyes.

If used on any woods with tannin naturally present it produces grays and bluish-blacks.

Dissolve one ounce to one quart of hot water.

Fustic

A natural dye – produces pleasant yellows and browns depending on the mordant.

Logwood

An extract from a tree in Mexico, this was an important natural dye.

It’s never been synthesized chemically and is still used in textile dyeing.

It produces shades from red through brown to almost black, depending on the mordant and concentration used.

If used without a mordant, it is not lightfast and for that reason was banned in England by an Act of Parliament passed in 1580.

When the proper mordanting procedures were developed using potassium dichromate and ferrous sulfate, the color is almost indestructible.

Sumac

This is a natural dye that is tannin-rich.

Use with any of the mordants that react with tannic acid to produce pinkish-browns.

Potassium dichromate is the preferred mordant.

Potassium Dichromate

This is historically an important mordant for tannin-rich woods like oak and mahogany.

Mix in various strengths since the color changes considerably depending on the concentration.

I recommend one ounce in a pint of water – then dilute to your needs. When used after a pretreatment of tannic acid, it can color any wood that does not contain tannin, such as maple.

Potassium Dichromate can be used with any of the natural dyes to deepen the color.

It also produces quite stunning colors used by itself.

Tannic Acid

Use this chemical for those woods that do not naturally contain tannin, such as ash and maple.

Sodium Carbonate

also known as washing soda, this chemical slightly darkens most woods.

The reaction is slow and may take several days to fully develop.

Sodium Hydroxide

The most common form is lye.

Red Devil brand is available at any Ace Hardware store.

Approximately one ounce to one quart is a good starting point. Gloves are mandatory as well as goggles for splashes.

Use on all woods that contain tannin such as oak, birch and mahogany.

Note on Sodium Hydroxide

Do not be tempted to use drain openers or oven cleaners.

These contain other chemicals that can cause problems with the clear topcoats of finishing material.

Red Devil is a brand that I use.

It’s also a good idea to neutralize the alkaline effect of this chemical with a solution of white vinegar.

Ammonia Hydroxide

This is purchased as 28% aqueous ammonium hydroxide.

You can buy it from chemical supply houses as ammonium hydroxide.

Ace Hardware sells “Janitor Strength” ammonia that’s 10% and will work just fine, though slower.

This is the chemical that produced the fumed oak effect popular in the first part of this century on Mission furniture.

You can use it on any wood that has a natural tannin content but the effect is best on white oak.

It can be brushed on, but fuming produces more subtle colors.

This involves placing the object inside a plastic tent along with open saucers of the ammonia.

The effect produces greenish – yellow colors immediately, and if left for several days the color can go to silvery dark browns.

Ammonia can also be used on cherry and mahogany.

I strongly urge that any ammonia procedure be done outdoors.

Walnut Husks

Gather walnuts in the fall, remove the husks (wear gloves) and bring them inside to dry for several weeks.

Put the dried husks in a glass jar about to the top, and then fill the jar with hot water.

Add one ounce of sodium carbonate (washing soda) and let the mixture sit in a cool, dry place for several weeks.

Strain the mixture through a fine filter, and then store it for use.

Use it like any other premixed water- based dye stain or with a mordant to improve the light-fastness.

Vinegar-Iron Mixture

This is a chemical treatment that is easy to make.

Shred one pad of 0000 steel-wool, and place in a jar and cover with white vinegar (Approximately one pint.)

If you put a lid on the jar, puncture holes in the lid so that the gases can escape.

Let this simmer for two days and then remove the steel wool and strain.

You will have a chemical (Iron acetate) that produces very positive blacks on some woods by reacting with tannin to form an insoluble and light-fast iron tannate.

Several applications may be needed.

If used diluted, you can get very good grays.

I have noticed that the coloring power of the solution decreases with time, so you should prepare only what you need for the job at hand.

Nitric Acid

Use this chemical in a 20% to 40% strength and always wear protective gear.

This chemical duplicates the look of aged pine beautifully.

Apply a wet coat to the wood and then heat with a hair dryer or heat gun to fully develop the effect.

The nitrate ion (NO3) is converted to NO2 which is brown.

I first heard about this treatment by a local artisan who uses it on curly maple gun-stocks and he says it’s a well-known treatment in that field.

If used without heat, it produces greenish yellow browns.

If you can get a stronger solution, 65 – 70%, you don’t have to heat it.

This strength is hard to get, because of shipping restrictions, so you may have to settle for strengths below 40%.

Applying the Dye/Mordants

I usually apply the mordant first, let it dry, and then apply the dye.

Sometimes subtle differences can be noted if you reverse the procedure.

A cheap synthetic bristle paint brush works well.

The best way to use the above chemicals is to experiment, keep accurate notes and write down the chemicals used on the back of your sample boards.

A good suggestion is to use a solid board, such as cherry, and treat it with one of the natural dyes.

Let it dry and then mask off several areas with masking tape and treat each area with a different mordant.

Using mordants in varying concentrations will produce different colors.

You can combine mordants, but apply them separately and never mix any of the chemicals together.

Below are guidelines to get started–they are not all that is possible with chemical dyeing and list only those woods which I have personally experimented with.

Ash

Does not naturally contain tannin, so use a pretreatment of tannic acid or any of the tannin-rich dyes like sumac.

A vinegar-iron mixture produces good browns. Potassium dichromate can be used, but treat first with tannic acid.

Ferrous sulfate produces colors from grayish-browns to black.

Beech

This reacts with almost all the mordants.

Lye produces a golden brown and potassium dichromate a grayish brown.

Ferrous sulfate produces a silver gray, but pre-treating with tannic acid will get a bluish black.

The vinegar/iron solution is similar to ferrous sulfate, but has greenish undertones.

This is a good wood for chemical dyeing.

Nitric acid produces almost the same color as lye.

Birch

The natural dyes in combination with the mordants produces colors ranging from yellow-gold to dark brown.

A good reddish brown is sumac with a potassium dichromate mordant.

Potassium dichromate gives a dark golden brown.

Ammonia gives a pinkish light brown.

Tannic acid pretreatment with a ferrous sulfate topcoat produces a good purple-black.

Butternut

Nitric acid applied and then heated results in a very pleasing golden-brown color.

The vinegar-iron solution gives an assertive black while ferrous sulfate a grayish-black.

Lye and ammonia produce a green-brown. Potassium dichromate produces a honey brown.

Cedar

Nitric acid applied, then heated with hair dryer when still wet gives a golden-orange aged effect.

Vinegar-iron will produce a weathered silver-gray.

Ferrous sulfate produces a green-gray.

Potassium dichromate gives a yellow brown but to kill the green undertone use with a tannic acid topcoat.

Cherry

This wood takes most of the chemical treatments nicely.

Ammonia gives a greenish brown.

A standard lye solution of two tablespoons to a quart produces a good orange brown with greenish undertones that simulates an aged look, but a stronger solution results in strong reddish-browns.

Potassium dichromate produces a dark brown.

Nitric acid will produce a chocolate brown and should be neutralized afterwards. (See below).

Any of the natural dyes will add subtle variations to these colors.

Maple

The natural dyes used with the mordants gives various shades of brown.

Lye gives a good pinkish brown.

Nitric acid produces an aged orange-brown but can be too strong so I “cool” it down with a dilute solution of ferrous sulfate Ferrous sulfate in normal concentration (two ounces to a pint of water) produces a greenish gray.

Tannic acid with a topcoat of ferrous sulfate results in a good black. The vinegar-iron solution produces grays.

A subtle brown can be achieved by logwood with alum as a mordant. Quilted, birds-eye and curly maple respond well to chemical dyeing.

Mahogany

This wood responds very well to potassium dichromate and depending on the concentration, produces honey orange to purple.

Pre-application of any of the natural dyes produces subtle variations with the potassium dichromate mordant.

The other chemicals will all darken mahogany.

Oak

Both oaks, red and white react to chemical treatment, but white oak more so, because of its higher tannin content.

The sapwood is a problem though, because it has no tannic acid and you may need to touch up these areas with alcohol soluble dyes after treatment. Potassium dichromate produces a good orange brown.

Fuming affords the most color variations, depending on the length of time left exposed to the fumes.

Pine

I treat this with the Nitric acid/heat method.

It produces an aged look that I cannot duplicate any other way. The vinegar-iron solution produces a good brown.

Any of the natural dyes combined with mordants will produce yellow, greens and browns.

Chemical treatment does not produce the “splotchy” effect that you can get with stains and dyes.

Poplar

The only way to get browns on poplar is to pre-treat it with tannic acid or a tannin-rich natural dye like sumac.

The iron-vinegar produces light green-grays.

Nitric acid applied wet then heated produces an orange-brown.

Lye will slightly darken poplar.

Sassafras

Lye gives a pink to this wood.

The vinegar-iron and potassium dichromate produce cold browns and ferrous sulfate a greenish brown.

Ammonia darkens it slightly.

Walnut

Produce an aged effect with the nitric acid treatment which lightens the walnut and turns it orange.

Potassium dichromate gives a good chocolate brown and the iron-vinegar solution a good deep black.

Lye darkens the wood slightly and gives a greenish tinge.

Conclusion

These are the colors you can produce, but keep in mind that hundreds of other colors are possible by stronger or weaker solutions of the mordants and chemicals.

Also, certain species such as cherry will produce different colors according to the geographical region where it was grown.

Different mahoganies like African, Honduran, and Philippine will all react differently.

After treating the wood, it’s a good idea to neutralize certain chemicals.

When using an acid or an alkali, you need to restore a neutral pH to the wood.

This is easily done.

If using ammonia or lye, a quick wash with white vinegar (which is a mild acid) will neutralize the effects of the alkali.

And if using nitric or sulfuric, wash it afterwards with a solution of baking soda dissolved in water. (About two ounces in a quart of water is fine).

If you don’t neutralize these chemicals, some of them react adversely with the finish or in the worst case, form salts in the wood which cause finish problems later.

With the other treatments, I would recommend a wash of distilled water.

Keep in mind that chemicals are not the only way to color the wood.

Sometimes a chemical treatment, followed by a stain or an aniline dye or all three, may give just the effect you want (If you do this, the oil-based stains should be the last treatment).

Arm yourself with plenty of scraps to experiment on, and remember that the best test pieces to use are those that are cutoffs from your project.